After nightfall on Monday, March 5, 1770, small groups of Bostonians armed with lead-weighted clubs, cudgels, and cutlasses started accosting lone British officers and soldiers in the city’s streets. Elsewhere in town, soldiers threatened and assaulted civilians. It was rumored that a missing sergeant had been murdered, while troops had beaten an oysterman bloody. By eight o’clock, angry men were confronting the redcoats outside Murray’s Barracks, a sugarhouse at Draper’s Alley and Brattle Street where parts of the king’s army were quartered. Several dozen more had gathered in Dock Square, old Boston’s commercial center by the harbor, many of them sailors wielding sticks and staves; some were breaking off the table legs from the market stalls. Windowpanes shattered under a barrage of snowballs and chunks of ice as men passed the house of an importer who had broken the boycott on British goods. The previous Friday, March 2, a long-standing dispute over scarce labor had erupted in a violent confrontation between dozens of workers and off-duty soldiers at John Gray’s ropewalk south of Milk Street. There had been further scuffles on Saturday, and although no lives had yet been lost, by Monday soldiers and civilians were spoiling for a fight.1

Shortly after nine o’clock, bells rang out across town—Brattle Square Church led, soon Old Brick Church fell in to the west, and then Old South, too. Bells pealing at nighttime usually signaled a fire. As many more residents rushed out of their homes into the late-winter night to haul fire engines and carry bags and buckets across the ice-covered streets, armed gangs began converging on the city center. Navigating by the light of the first-quarter moon, the men joined a fast-swelling crowd in front of the Custom House at the northeast corner of King Street (today’s State Street) and Royal Exchange Lane. As young Benjamin Davis soon realized, “There is no fire. It is the soldiers fighting.”

Outside the Custom House, the imposing brick building that held the customs records and revenue from tariffs, a crowd of several hundred and growing were facing off against nine British soldiers. When the bells had started ringing, Captain Thomas Preston, the forty-year-old Irish captain on duty, had marched a corporal and six grenadiers of the 29th Regiment of Foot from the nearby main guardhouse through the surging mass of agitated people to support Private Hugh White, the lone British sentry at the Custom House. White had earlier struck a wigmaker’s apprentice with his musket after the boy had heckled a British officer; before long, an expanding crowd was lobbing snowballs and abuse at him, making the sentry fear for his safety. He had now fallen in with the tall grenadiers to form a semicircle, their backs to the building, muskets loaded and bayonets fixed. Many men in the mob also carried weapons—from the sticks some had been wielding all evening to the knives and Highland broadswords others had slipped under their coats before heading out that night. At least three men in the crowd as well as three of the soldiers now facing them had been among those exchanging blows at the ropewalk the previous week.

The site of their renewed encounter, the Custom House, symbolized the detested imperial revenue system that Britain had saddled on its thirteen Atlantic seaboard colonies after its victory in the Seven Years’ War, which had ended in 1763. Britain wanted the colonies to share in the expense of the victorious war and their future defense, not least by contributing towards the costs of a 10,000-strong British army stationed in America. For years, Massachusetts had played a leading role in opposing these new imperial policies, by means both legal and extralegal. Bostonians remonstrated against the Stamp Act, which had imposed a new tax on every piece of printed paper. After that law was repealed, they took issue with the Townshend Acts, which levied duties on imports such as glass, lead, and tea. They petitioned the imperial government and persuaded eleven colonies to adopt a non-importation ban. Crowds of men and women rioted, damaged property, and intimidated and injured customs officials as well as violators of their boycotts on British goods. Just a month earlier, a thousand-strong crowd had besieged the house of a customs informant who had reported on fellow Americans guilty of violating the imperial tax code; when he shot into the mass of people, an eleven-year-old boy was martyred.2

The turning point had come in 1768, when the British government sent several thousand troops to Boston to police the revenue system. For the Crown to show its military might in Boston in the manner it had previously done in Ireland or Scotland was a provocative move. In a town of 15,000 or 16,000, there now were as many imperial soldiers as there were white male residents above the age of sixteen. It did not help that among the troops were numerous Irish, and when the Afro-Caribbean drummers who served in the British regiments carried out disciplinary floggings of white soldiers on the Common, it offended Bostonians’ sense of the social and racial order.3

British soldiers were quartered not just in barracks but in private homes and warehouses, too. The army posted sentries outside public buildings. Troops established checkpoints, questioning pedestrians and searching carriages. Drunken soldiers fueled petty crime and prostitution. Redcoats beat male residents; women faced attempted abductions and sexual assault. Soldiers who were off duty competed with maritime laborers for scarce employment, triggering violent altercations like the one that had occurred at the ropewalk. Locals routinely harassed the redcoats, hurling stones at those detested “Bloody Backs.” Neither could the troops entirely prevent attacks on customs officials and their informants. Indeed, the soldiers seemed to symbolize the erosion of London’s authority as much as they demonstrated imperial strength. As Benjamin Franklin had predicted at a recent House of Commons inquiry, British troops sent to America would “not find a rebellion; they may indeed make one.”4

That early March night, John Adams, the ambitious Braintree lawyer who had moved his young family to Boston in 1768, described the sounds of rebellion near the Custom House: “[T]he people shouting, huzzaing, and making the mob whistle as they call it, which when a boy makes it in the street, is no formidable thing, but when made by a multitude, is a most hideous shriek, almost as terrible as an Indian yell.” The mob taunted the redcoats: “Come on you Rascals, you Bloody Backs, you Lobster Scoundrels, Fire if ye dare, G—d Dam’n you, Fire and be damned; we know you dare not.” They knew that only civil magistrates could authorize soldiers to use force to disperse an unlawfully assembled crowd. They also knew that Boston magistrates were unlikely to endorse the use of such force in the current political atmosphere. What they perhaps didn’t realize was that any soldier judging his life to be in imminent danger had the right to fire in self-defense.5

Captain Preston, desperate to calm heated tempers, was pleading with the civilians to disperse when a shot rang out. One of the grenadiers appeared to have been hit by an object—perhaps a snowball or a piece of ice or white-barked wood that either struck him or clipped the muzzle of his musket. According to most later reports, he had slipped on the ice, some saying his musket had briefly escaped his grasp. As he got up and recovered his firearm, he discharged a shot, whether deliberately or by accident. No one seemed to have been hit. There was a brief pause while many in the crowd looked for cover. Some, though, moved towards the soldiers, and one or two apparently even sought to wrestle their muskets from them. Several Boston militia drummers started beating to arms. A man in the crowd lashed out at the soldier who had fired; in the process, the assailant hit Preston’s arm hard with his club. Then the grenadiers fired a round of shots.

By the time Preston managed to stop the firing, three men lay dead in the snow, two more were dying, another half dozen were wounded. One bullet had hit the rope maker Samuel Gray, “entering his head and beating off a large portion of his skull.” Through the streaming blood, one bystander ascertained a hole “as big as my hand.” Crispus Attucks, a forty-seven-year-old former slave of Native American and African heritage who was passing through Boston, was felled by two bullets to his chest, one of them “goring the right lobe of the lungs and a great part of the liver most horribly.” Two bullets killed James Caldwell, a ship’s mate. Apprentice Samuel Maverick, seventeen, was hit in his stomach by a bullet that had ricocheted off a wall; although a doctor was able to remove the projectile, the teenager died in the morning. Patrick Carr, a thirty-year-old Irish immigrant employee of a leather-breeches maker, was hit by a musket ball fired quite possibly by a fellow Irishman. The bullet “went through his right hip & tore away part of the backbone & greatly injured the hip bone.” Carr died ten days later.6

Henry Prentiss had at first assumed the soldiers’ guns were not loaded. But as men around him fell to the ground, he realized that he was witnessing “a scene the most Tragical, of any that ever the Eyes of Americans beheld . . . to see the blood of our fellow Citizens flowing down the gutters like water.”7

* * *

By the spring of 1770, Americans had developed a deep sense of grievance against an empire that taxed them without their consent and sent an army in peacetime. From Rhode Island to the South, colonists intimidated customs officials and damaged property. In 1768, merchants in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia had renewed their resolve not to import British goods, soon to be joined by Virginia, Maryland, and South Carolina. Although Britain partially repealed the Townshend Acts in response to the boycott, the tax on tea, which raised the largest sums of money, remained in place. With imperial troops arriving imminently, the Boston town meeting called an extralegal convention of all the towns of Massachusetts, which promptly condemned “raising or keeping a standing army” without the people’s approval. By 1770, then, Boston’s neighboring towns were primed to respond to any further escalation of the brewing crisis—and whatever might happen in Boston would resonate across the colonies.8

As news of the fatal shootings spread through Boston that March night, the church bells rang again. Town leaders prepared to summon thousands of men who were standing by in surrounding towns to confront the redcoats. At the same time, the sound of British drums beating to arms had soldiers scrambling across the city. In their quest to reach the center, some wielded their swords to clear a path through hostile crowds; a few took punches from irate citizens. Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson, who had rushed to the scene of the shootings, eventually managed to deescalate the situation by appealing to Bostonians from a first-floor balcony: the rule of law would prevail, a full inquiry would be held, and they should disperse peacefully. Most did as asked, but a hundred men or so stayed until the early hours while an initial inquest was conducted. By three a.m., Captain Preston was taken into custody; the following morning, the eight soldiers, too, were arrested and thrown into jail. The beacon to summon armed colonists to Boston was never lit, and no further shots were fired in anger that night.9

Participants and witnesses understood instantly the significance of what had occurred on King Street. Over the following weeks, both sides sought to shape the story of that evening in an effort to win the battle of public opinion, not least by publishing the depositions they solicited from local inhabitants and soldiers. Town leaders accused the British occupiers of a pattern of oppression and cruelty against innocent citizens that had climaxed in the deadliest confrontation thus far, what they quickly called the “bloody massacre.” Pro-British accounts, by contrast, emphasized the premeditated nature of the incident, with armed civilians provoking soldiers into a fight that would lead to their eventual withdrawal. The morning after, the British indeed began evacuating their troops, albeit but a few miles to the Castle Island barracks. The colonial official, Andrew Oliver, recognized the ambiguity of the situation: “[I]t is difficult to determine which were the Aggressors.” As Oliver was now laid low with the gout, “the Reports of killed and wounded,” he reflected, “painted in my Imagination all the Horrors of a civil War.”10

One week after the shootings, on March 12, the Boston Gazette published the single most influential anti-British account. Boston, the paper reported, had witnessed “a most shocking Scene, the Blood of our Fellow Citizens running like Water thro’ King-Street, and the Merchants Exchange.” The story was soon reprinted in other colonies, where resentment against the overbearing empire was already brewing, as well as in the British press. The article, set within thick black borders, also covered the funeral rites of the massacre’s first four martyrs, attended by more than 10,000 people, and was illustrated with a woodcut showing four coffins with the initials of the slain, skulls and bones, and an hourglass and scythe.11

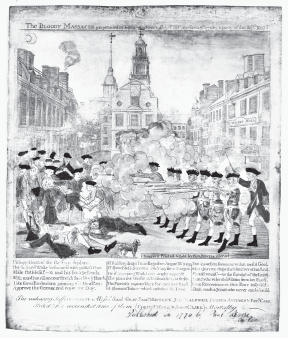

Whereas few today will recollect the Boston Gazette’s prose account, most Americans and many in Britain are probably familiar with Paul Revere’s iconic representation of the bloody massacre. The Boston silversmith and engraver adapted a composition by Henry Pelham to produce a brilliant visual polemic that deviated in significant ways from reality. This engraving, advertised for sale only three weeks after the event, shows an unarmed crowd of exclusively white, well-dressed gentlemen (and one concerned woman in a shawl)—not the missile-hurling motley crew of waterfront boys and men, apprentices, and mechanics, including immigrants and former slaves, that had actually assembled—who face seven aggressive British soldiers arrayed like a firing squad. A sniper has discharged a gun from a window of the Custom House, now also labeled “Butchers Hall.” Colonists often had their copies of the engraving hand-colored, with the red of the British uniforms matching the blood oozing from wounds in the victims’ heads, chests, and stomachs.12

British officials delayed the trials of Captain Preston and his men until the fall, hoping that by then tempers might cool down. Supported by the Sons of Liberty, John Adams agreed to serve as attorney for the accused soldiers: everyone, he believed, deserved a fair hearing. Adams argued that the redcoats had acted in self-defense in the face of a provocative mob; at worst the soldiers were guilty of manslaughter, not murder. He alluded to the limits of troops performing urban anti-riot duty: “[S]oldiers quartered in a populous town, will always occasion two mobs, where they prevent one.—They are wretched conservators of the peace!” The jury acquitted Preston and six of the soldiers. The two men convicted of manslaughter pleaded benefit of clergy, a device that allowed for their capital sentences to be commuted; they were released after having their thumbs branded.13

In subsequent years, John Adams’s thoughts kept returning to that violent and defining evening. The Boston Massacre had become an annually commemorated event, complete with orations, the display of relics, and guided tours of the bloodied site. On its third anniversary, in 1773, Adams recalled how much anxiety his role as defense attorney for the British soldiers had caused him. At the same time, he proudly reflected, ensuring that the defendants received a fair trial had been “one of the most gallant, generous, manly and disinterested Actions of my whole Life.” He had rendered a truly patriotic service, for a death sentence would “have been as foul a Stain upon this Country as the Executions of the Quakers or Witches, anciently.” In his diary Adams noted, “as the Evidence was, the Verdict was exactly right.” Yet this was “no reason why the Town should not call the Action of that Night a Massacre.”14

Adams’s thoughts may have sounded contradictory, but they illuminate the reason the Boston Massacre has remained so iconic over the centuries. The shootings had been the unplanned product of the violence of imperial oppression colliding with the violence of colonial resistance. For those who lived through revolution and war, the wounds sustained by eleven men that night—wounds that foreshadowed the disfiguring and lethal injuries soon to be suffered by tens of thousands—would come to serve as a metaphor for the wounds torn open in Americans’ relations with their fellow subjects on both sides of the Atlantic. For the Revolutionaries, the deaths on King Street symbolized colonial Americans’ resistance in the face of wanton British cruelty. That allegation was wrong, as Adams had proven in court, but it nevertheless stuck. By 1786, when Adams was serving as the first United States ambassador to the Court of St James’s, he summed up the event’s complex legacy in one bold judgment: “On that night the foundation of American independence was laid.”15

* * *

In the popular memory of the American Revolution, a quarter millennium on, the Boston Massacre is something of an anomaly: it is a violent event we acknowledge and remember. But the Revolution was also violent in ways we don’t remember, and perhaps can’t even imagine, because they have been downplayed—if not written out of the conventional telling altogether. Although the American Revolution has been continuously invoked since the eighteenth century in the name of all manner of causes—the Tea Party’s opposition to health care reform being perhaps the most salient modern example—its inherent violence has often been minimized. The result has been the perpetuation of an overly sentimental narrative of America’s originary war. Even the portrayals of George Washington’s hungry, ill-clad soldiers, their feet reddening the snow at Valley Forge, nostalgically evoke martyrs rather than battle-bloodied warriors. American popular memory of this era tends to focus on great white men debating independence in Philadelphia’s hallowed halls or on Mount Vernon and Monticello, “as if the war,” writes the historian Edward Larkin—and, we should add, American-on-American violence—“were incidental to the Revolution.”16

There are good reasons why Americans portray their revolution and war for independence as an uplifting, heroic tale, as the triumph of high-minded ideals in the face of imperial overreach, as a unified and unifying nation-building struggle to deliver a free and independent United States. But, in doing so, they risk neglecting its divisive and violent strands. To understand the Revolution and the war—the very birth of the nation—we must write the violence, in all its forms, back into the story. That is my aim in this book.

By “violence,” I mean the use of physical force with intention to kill, or cause damage or harm to people or property. I also mean psychological violence: the use of threats, bullying tactics, and brutality to instill fear in people and influence their conduct and decisions. It was through campaigns of terror that the American Patriots enforced their revolution internally against the American Loyalists. It was through the longest war ever fought on American soil that the Patriots defended their new nation’s independence from the British Empire. And it was by distinguishing acceptable from illegitimate forms of violence that the Patriots sought to fight that war in ways that matched their political ideals: by highlighting the enemy’s brutishness while striving to stay within the limits permitted by the prevailing codes of war, the Revolutionaries tried to win the moral war that accompanied the war on the ground. After a decade of civil war, further violence against the Revolution’s losers would complicate the transition to peacetime nation building. When at war’s end Americans remained conflicted about the appropriate uses and limits of violence, it was clear that the wounds they had delivered and sustained—physically, psychologically, metaphorically—had profoundly shaped the nature, outcome, and legacies of their foundational conflict.17

I first became curious about Revolutionary-era violence a decade ago, as I was conducting research for my previous book, Empires of the Imagination. While studying examples of eighteenth-century art, I encountered a series of monuments to American Loyalists in churches and cathedrals across England. They ranged from little stone tablets in provincial churches to a substantial marble sarcophagus in Westminster Abbey, but they shared one common feature: they all told stories of American Loyalists being brutally treated—hunted, dispossessed, and, finally, driven out of the country, afraid for their lives. Evoking an era when there was “scarcely . . . a village in England without some American dust in it,” these memorials all spoke of the psychological and physical violence inflicted on individuals who had opposed the Revolution.18

Those harrowing accounts of persecution and suffering stayed with me, not least because they were hard to reconcile with the conventional narrative of a restrained, largely nonviolent revolution. Eager to uncover the stories behind the memorials, I turned to the archives and found that many of the detailed accounts the Loyalists had produced during and immediately after the war reinforced what I had seen. These reports described scenes of humiliation, bullying, torture, and even the occasional lynching. Scholars, by contrast, had given limited space to such American-on-American violence. Participants at the time referred to the American Revolution as a civil war, and writers over the past century have occasionally spoken of it in these terms. Yet the wider American public, and even many historians, still seem reluctant to embrace the notion of civil conflict as a way to describe the Revolution. Perhaps that’s no surprise, if only because seeing the Revolution as America’s first civil war forces us to confront the terror at its very core.19

Reading further in the participants’ accounts, we find that American Patriots, who tended to remain silent about the violence they meted out to Loyalists, dwelled with passionate indignation on the cruelty that they themselves suffered at the hands of the barbarous British and their Loyalist, Native American, and German auxiliaries. The Patriots accused the British of indiscriminate plundering and destruction, battlefield massacres, rape, prisoner abuse, even the deportation of American captives to Asia and into slavery in Africa. They also grappled with the quandary of how to answer such abuse—for violence flowed in all directions.

Reports by British political and military leaders confirm the stories of the American Patriots’ brutality towards their Loyalist neighbors. They also describe acts of cruelty against British combatants and captives by American Revolutionary forces. At the same time, they reveal the strategic and ethical dilemma that government ministers and army officers faced in orchestrating a counterinsurgency against white, Protestant, Anglophone fellow subjects—all while their own nation was deeply divided. And both American and British portrayals allow us to reconstruct at least in part the contributions and sufferings of black and Native American populations on both sides of the conflict.

The sheer scale and pervasiveness of the violence generated by the Revolution’s partisan fury and by more than seven years of war is manifest in written accounts and imagery from the period. The correspondence of leaders, the diaries of individual men and women, political pamphlets, popular prints, and congressional records all vividly convey the swirl of brutality that swept up all sides. As with the Boston Massacre, these sources also show us how violence shaped the stories that participants were telling about revolution, counterrevolution, and war. Yet neither the Revolution’s academic historians nor its popular chroniclers have studied this aspect of the war in a systematic way.

In this book, we will follow protagonists to battlefields and army camps; to prisons on land, underground, and offshore; onto farms and into homes. We will discover how all parties used terror: Patriots against Loyalists; British forces and their Loyalist and German auxiliaries against rebel combatants, captives, and civilians; General Washington’s Continental Army against Native Americans; white and black Southerners against one another. We will take a close look at the physical evidence of violence: the bayonet wounds in a soldier’s mangled corpse; a girl’s story of her rape by enemy soldiers; the emaciated, lice-ridden figures of prisoners of war; the decapitated head of a slave turned spy warning others not to join the British; columns of smoke rising over New England seaports, Southern plantations, and the vast cornfields of Iroquoia. Loyalists, women, former slaves, and rebel captives each experienced distinctive forms of violence. And all sides spun narratives of persecution and atrocity, of suffering and sacrifice, of community building and revenge, and of attempts to exercise restraint—some successful and others decidedly not.

* * *

If violence was fundamental to how American Patriots and their enemies experienced America’s founding moment, why has it been moved to the margins of the story that we typically hear? First, in postwar America, the Revolution’s Loyalist losers, and the violence they had endured, were systematically excluded from public discourse. As R. R. Palmer put it in his classic The Age of the Democratic Revolution over half a century ago, “The ‘American consensus’ rests in some degree on the elimination from the national consciousness . . . of a once important and relatively numerous element of dissent.” A British tendency to turn a blind eye to an unprecedented defeat is also partly to blame. Britain’s imperial loss occurred despite putting one in every seven or eight eligible men under arms, and recruiting large auxiliary forces in Germany to fight alongside white Loyalists as well as Native Americans and former slaves. As late as 1883, Sir John Seeley, the distinguished Cambridge historian of the British Empire, described the American Revolution as an embarrassing episode, “which we have tacitly agreed to mention as seldom as we can.”20

Over time, even the Revolutionary-era emphasis on the blood that the Patriots shed in defense of their new republic has yielded to a strangely bloodless narrative of the war that mirrors the image of a tame and largely nonviolent Revolution. The magisterial accounts by later twentieth-and early-twenty-first-century historians such as Bernard Bailyn, Gordon Wood, and T. H. Breen that dominate American college classrooms focus on the Revolution’s ideas and ideals and largely tune out the physical and psychological trauma experienced by so many participants. Meanwhile, bestselling biographies of the Founding Fathers continue to romanticize the Revolutionary era.21

Whether in their academic or public discourse, Americans do not generally shy away from discussing violence in their history and culture, a tendency that applies as much to the history of colonization, the frontier, and slavery up to the Revolution as it does to the violence that characterizes the modern United States at home and in its conduct overseas—from the prevalence of gun-related deaths to the controversies over preemptive military action and drone strikes. Yet Americans are curiously silent when it comes to their nation’s birth. As a historian of nationalism in the early republic has demanded, “[W]e must seek to understand the tie between nationalism and violence” in the United States, especially given that few nation-states “are as renowned for their proclivity for violence.”22

This partial blindness contrasts particularly glaringly with today’s general awareness of the battlefield carnage, the ordeal of POWs, and death in the American Civil War. Indeed, acknowledging the undeniable horrors of that war, in some ways, has made the need for an immaculate conception all the more acute. “For many Americans the Revolution is their last great romance with war,” writes the scholar Carol Berkin, as they imagine it as “quaint and harmless,” an image that appeals in an “era of genocidal wars, terrorism, and heated debates over the meaning of patriotism.” But it is precisely because we face an uncertain world of insurgencies and civil wars, stalled revolutions and failed states, that Americans should confront their own tumultuous birth. It is time to strip some of that lingering romanticism from America’s foundational conflict.23

* * *

Writing violence back into the story of the Revolution reminds us that America’s war for independence caused proportionately more human suffering than any other war in American history except the Civil War. Because to modern eyes the absolute numbers involved look comparatively small, it is easy to forget that with an estimated 6,800 to 8,000 Patriot battle deaths, 10,000 killed by disease in camps, and up to 16,000 or even 19,000 who perished in captivity, the number of Patriot soldiers killed in the Revolutionary War would be well over 3 million in terms of today’s population—and significantly more than that if we consider Patriot deaths as a proportion of only the Patriot population in 1775 or 1783. More than ten times as many Americans died, per capita, in the Revolutionary War as in World War I, and nearly five times as many as in World War II. The death rate among Revolutionary-era prisoners of war was the highest in American history. In addition, at least 20,000 British and thousands more American Loyalist, Native American, German, and French lives were lost. The Revolution exacted further human sacrifice when at war’s end approximately 1 in 40 Americans went into permanent exile, the equivalent of some 7.5 million today.24

As the Boston Massacre demonstrates, it is tempting for humans engaged in a struggle to remember the violence suffered by their own side but to neglect that endured by others. It is crucial, therefore, that we consistently look at the Revolutionary era through multiple lenses: American Patriots, American Loyalists, and the British, as well as Native American, black, and German participants. This enables us to transcend nation-centered and nationalist narratives, whether American or British, with their various myths, exaggerations, and blind spots. And it helps us avoid falling into the trap of categorizing either side as simply victims, traitors, or cruel aggressors in what Americans call the Revolutionary War and the British know as the American Rebellion or the War of American Independence. It is in this respect that—as a German-born specialist in British history who did not grow up with the national myths of either Britain or America, but who for the past two decades has researched and taught on both sides of the Atlantic—I hope to bring a fresh outlook.25

American casualties of British atrocities, along with the victims of General Washington’s campaigns of terror in Indian country, urge us to keep multiple perspectives in mind. So do the American Loyalists. For, by the 1770s, as thousands of ordinary Americans joined the insurgency against what they saw as imperial oppression, between one-fifth and one-third of the white population continued to support Britain in sentiment, if not always in deed. Others were not yet particularly invested in either cause, or would change sides. But anyone who was not explicitly a Patriot risked being branded and persecuted as an enemy of America. As one New Yorker wrote to a London acquaintance, explaining his quandary: “I have no relish for civil Wars & there is no such thing as being a looker on.” When the Anglo-American crisis escalated, Patriots targeted both their outspoken opponents and the as-yet-uncommitted—and they did so not just with moral suasion but also with threats and physical violence. There was no guillotine in Boston, New York, or Charleston, as there would be in Paris two decades later. Yet forging the new American nation entailed the forced exclusion not only of black slaves and Native Americans but also of white Euro-Americans who did not subscribe to the Revolutionary project. The Revolution’s noble ideals aside, violent incidents were not the unfortunate exceptions to an orderly, restrained revolution. Rather, and especially where Loyalists were concerned, they were the norm. Both the Revolution’s supporters and its opponents came to experience its inherent violence as a defining characteristic that gave meaning to their struggles.26

The Boston Massacre also shows us that violence cannot be separated from stories about violence. The physical reality of violence and the political, polemical, and moral uses to which it was put were inextricably intertwined. Narratives of violence, as much as ideology, helped shape allegiances and mobilize support, whether for the cause of independence or empire. Stories of persecution, suffering, and sacrifice empowered American Patriots and Loyalists—and also Britons—to make sense of the Revolution, civil war, and colonial rebellion. And it was through such stories that they each made moral claims, seeking to win the support of the American population and gain the sympathies of audiences in Britain and Europe. For this was a war of persuasion as much as strategy, manpower, and logistics. It mattered not only how each side conducted the war—materially and ethically—but what stories each could convincingly tell about its own and its opponents’ conduct.27

A more honest rendering of the era enables us to see, then, that the American Revolution was not some glorious exception. Like other modern revolutions, and for all its transformative (and positive) effects, it required violent escalation and terror to sustain itself and combat its domestic enemies. From the victors’ perspective, the prize of enjoying liberty and independence justified the fierce treatment of fellow Americans. At the same time, though, Washington, Adams, and their fellow leaders were adamant that they must fight the war against Britain in ways that matched their ideals. By following a policy of humanity, as Adams put it, vis-à-vis enemy combatants and captives, they must out-civilize the British. To be sure, reality often fell short of worthy aspirations. But at the moment of America’s violent birth, the founders launched their new nation with a sense of moral purpose. If the idea of the United States is grounded not in a “common ethnicity, language, or religion” but instead in a “set of beliefs,” as the historian Gordon Wood reminds us, we should include among these beliefs the conviction that a society must uphold its core values even—and especially—in times of war. Projecting the power of America’s example, as much as the example of her power, was a foreign policy principle the founders embraced; it is a notion that modern leaders would do well to remember.28

Painting an unvarnished picture of the Revolution helps us at once recognize its defining ferocity, appreciate its lasting accomplishments, and discern its complicated legacies. Throughout the war, Americans wrestled with questions of violence and restraint against enemies foreign and domestic. The postwar United States, unlike France, Russia, and other revolutionary societies, avoided dictatorship, a military regime, and—with the partial exception of the War of 1812—more civil war. But this outcome also entailed unresolved contradictions for America’s emerging empire of liberty, most painfully and violently the entrenchment and extension of slavery, and the exclusion and soon the decimation and “Removal” of Native Americans. And as the white majority population set about building a nation after a decade of civil conflict, both the Revolution’s winners and its losers bore the physical and psychological scars of war, persecution, and terror—scars that were selectively acknowledged at best, and often partially covered.

Generations of Americans since have grappled with their nation’s violent beginnings in a balancing act of remembering and forgetting. Repressing trauma, denying terror, and whitewashing violence have helped foster a powerful myth of American exceptionalism that fits the heroic narrative of the original war. But looking afresh at the scars of independence through the eyes of participants on all sides helps us untangle the inherent tensions between America’s moral objectives and her violent tendencies. As we engage a world riven by wars, civil conflicts, and insurgencies, understanding how violence relates to nation building, and how it is represented and remembered, remains as critical as ever.29